For quite some time, I’ve wanted to write about semantic model memory optimization in Power BI and Fabric.

It’s a topic that keeps coming up in projects, training, and community conversations – and one where many people struggle once their models start to grow.

Before I could write about optimizing semantic models, I needed a proper lab environment:

- large enough to be interesting

- realistic enough to expose real problems

- flexible enough to support multiple modeling patterns

This blog post is about how I built that lab environment in Microsoft Fabric.

The actual optimization patterns, VertiPaq analysis, and semantic modeling techniques will come later – including a series of posts on the official Tabular Editor blog.

If you’re reading this because of those posts, this is the “how did you build the dataset?” part.

A transparency note (important)

Before we go any further, I want to be completely transparent:

The notebooks and SQL views used in this lab were created with extensive help from ChatGPT.

I am not a Python developer, and the majority of the Spark and SQL code is AI-generated.

My role in this project was not to hand-write Spark code, but to:

- define requirements and constraints

- validate results

- iterate on design decisions

- debug data quality issues

- decide what is correct and what is acceptable

AI helped with syntax and structure.

The responsibility for architecture, correctness, and modeling decisions is still mine.

I’m being explicit about this because I believe this reflects how many of us actually work today – and because the value of this project is not the Python code itself.

Why build a dedicated lab?

If the goal is to talk about semantic model memory, small demo datasets don’t really help.

I wanted a dataset that would:

- span many years

- include bad data

- allow “bad” modeling choices on purpose

- scale to billions of rows

That way, memory behavior becomes visible and measurable — not theoretical.

For this, the NYC TLC Yellow Taxi Trip Records are ideal:

- public

- well-known

- large enough to stress real systems

The dataset spans from 2009 to 2025 and contains more than 1.8 billion rows, with around 40 GB of source parquet files.

High-level pipeline

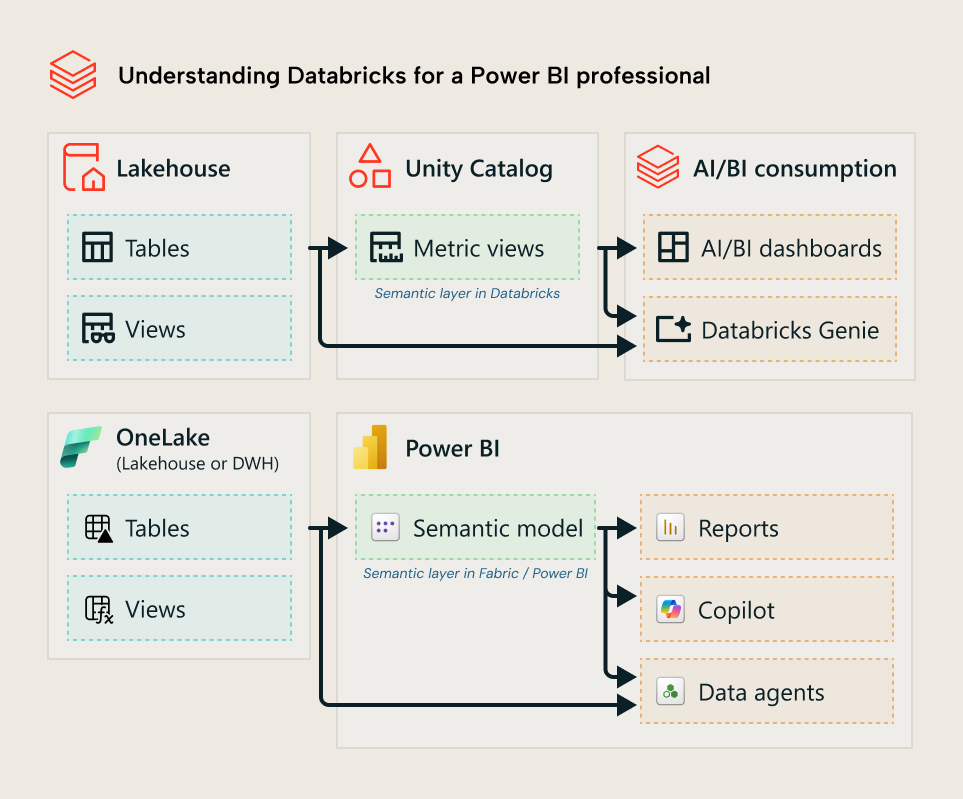

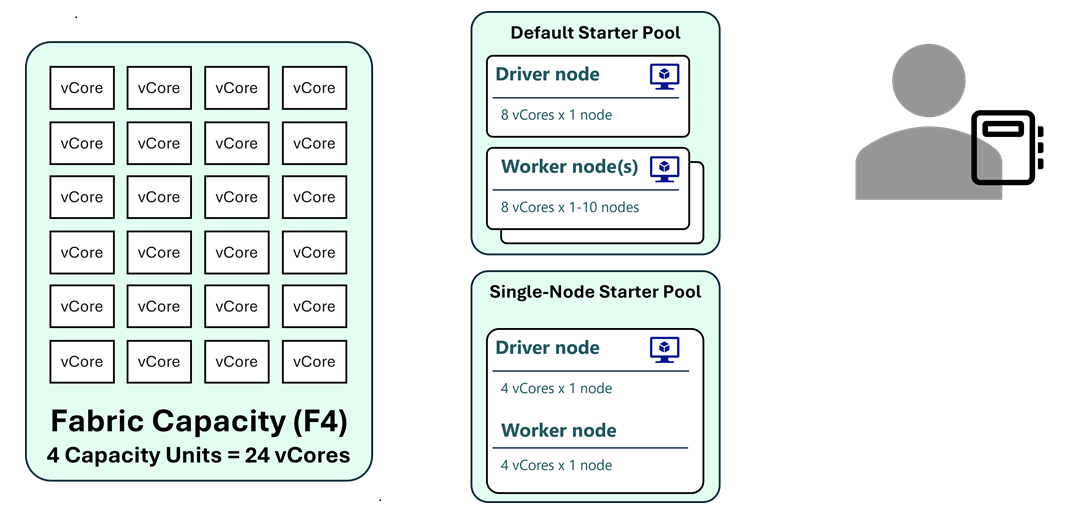

The lab is built entirely in Microsoft Fabric, using notebooks and Delta tables.

At a high level, the pipeline looks like this:

- Ingest raw parquet files into OneLake

- Unify 17 years of schema evolution into a single structure

- Build a wide Gold fact table (intentionally not optimized)

- Create dimensions for later semantic modeling

Each step is implemented as a Fabric notebook.

Step 1: Ingesting the raw data

The first notebook is intentionally boring — and that’s a good thing.

Its only job is to:

- download the public parquet files over HTTPS

- copy them into OneLake

- store them in a Hive-style folder structure by year and month

No transformations, no cleansing, no schema changes.

This preserves the raw data exactly as published and gives a clean starting point.

Step 2: Unifying the schema (where most of the work happens)

This is the most important notebook in the entire project.

Over the years, the TLC dataset has:

- renamed columns

- changed data types

- added new fields

- removed old ones

- used different naming conventions

If you simply union all files together, you don’t get a usable dataset.

In this notebook, I:

- scanned schemas across all months and years

- identified schema variants

- normalized column names

- aligned data types

- introduced missing columns with nulls

- handled legacy field names

The goal was not to clean the data perfectly, but to make it consistent.

At the end of this step, I had a single, unified dataset spanning 2009–2025 that Spark could actually work with.

Step 3: Creating a deliberately “bad” fact table

This step is counterintuitive if you’re used to building production models.

Instead of optimizing early, I intentionally created a wide fact table that includes:

- high-cardinality columns

- GUID-like identifiers

- string-heavy attributes

- redundant fields

- unnecessary numeric precision

Why?

Because the goal of this lab is to observe memory behavior, not to avoid it.

If the dataset is already perfectly optimized, there’s nothing interesting to analyze later.

This table is large by design – hundreds of gigabytes – and that’s intentional.

Step 4: Building dimensions (and handling bad data)

The final notebook creates the supporting dimensions:

- Date

- Time of day

- Taxi zone (pickup and dropoff)

- Vendor

- Rate code

- Payment type

This is also where real-world data quality issues show up.

For example, the dataset contains a small number of valid but implausible dates:

- years far outside the dataset’s range (e.g. 2001 or 2098)

Rather than filtering rows out or extending the date dimension indefinitely, I chose to:

- introduce a single Unknown Date member

- explicitly map out-of-range values to it

This keeps referential integrity intact and reflects a modeling decision many of us face in real projects.

Why this lab matters

At this point, I have:

- a large, stable dataset

- real schema evolution

- real data quality issues

- intentional modeling anti-patterns

Most importantly: I can now build multiple semantic models on top of the same data and change only the modeling decisions.

That’s the foundation for the next part of the journey.

What comes next

This blog post is about building the lab.

The next step is using that lab to explore:

- Import vs Direct Lake

- model size vs SKU limits

- dictionary sizes and cardinality

- date/time modeling choices

- high-cardinality columns

- refresh behavior and partitioning

Those topics will be covered in a series of posts on the Tabular Editor blog, where the focus shifts from data engineering to semantic modeling.

If you’re mainly interested in how the data was prepared, this post and the accompanying GitHub repository should give you full transparency.

Final thoughts on using AI

One last note.

Using ChatGPT did not remove complexity from this project – it moved it.

Instead of spending time on syntax, I spent time on:

- asking better questions

- validating assumptions

- interpreting results

- deciding what to keep and what to change

That trade-off is exactly why this lab exists.